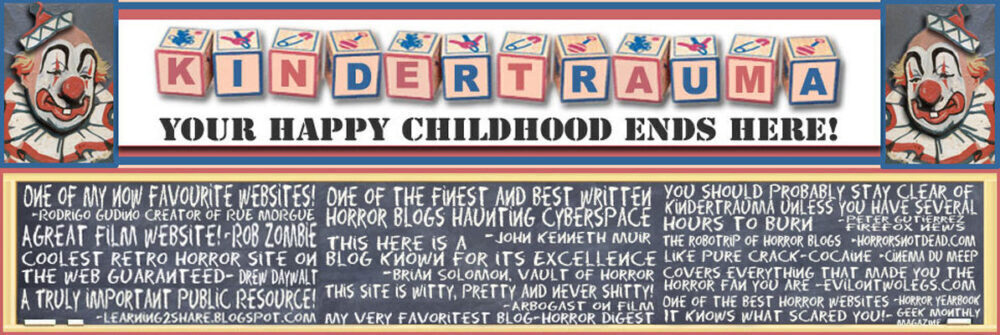

UNK SEZ: You may want to hold onto your hats because we've got some exciting news! KINDERTRAUMA: WE KNOW WHAT SCARED YOU is a forthcoming documentary all about the movies, TV shows and general media that scared us all as children and it's executive produced by your old pals at Kindertrauma! You can be a part of this wonderful project by joining our Kickstarter HERE and choosing the level of kinder-contribution that best suits you! Thanks in advance for all of your much appreciated support and make sure you follow KINDERTRAUMA: WE KNOW WHAT SCARED YOU on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook for exclusive clips and updates!!!

You must be logged in to post a comment.